Do Not Break the Dream

Welcome to the Hammer Party #4, July 2021

Welcome to the Hammer Party.

Some news first: my novel THE LAST KING OF CALIFORNIA will be published in the UK by Simon & Schuster, looking at a May 2022 release date. Set in the aftermath of SHE RIDES SHOTGUN, it’s a rather apocalyptic crime novel about a young man named Luke who has never recovered from witnessing his father commit a horrific crime when Luke was only seven years old. He is now returning to the Inland Empire for the first time since he was a child. He is an outcast from his outlaw family who comes home just as their way of life is threatened both by the reunified Aryan Steel gang and the ever-growing California wildfires. It has yet to be described as a “laff-riot.”

Meanwhile, I’m putting the final touches on my next novel, EVERYBODY KNOWS, with hopes of taking it to market in the next few months. It’s an epic LA crime story - I hesitate to say more right now - and I’m extremely excited for it to hit the world. My hope is that LAST KING will be published in the US after I find a home for EVERYBODY KNOWS.

In other news, I sat down last month with my good friend Jen Johans to talk about the great Preston Sturges. She let me rant about his movie Sullivan’s Travels, which, were I made dictator of Hollywood, I would force people to watch over and over again until the word “prestige” is abolished from our vocabulary.

I also talked with Eli Cranor as a part of his terrific Shop Talk series. It was a long talk about process in which we covered some of the stuff I’ve already talked about in this newsletter. It also led me to spend more time thinking about these things, thus the below thoughts:

Thoughts on Writing

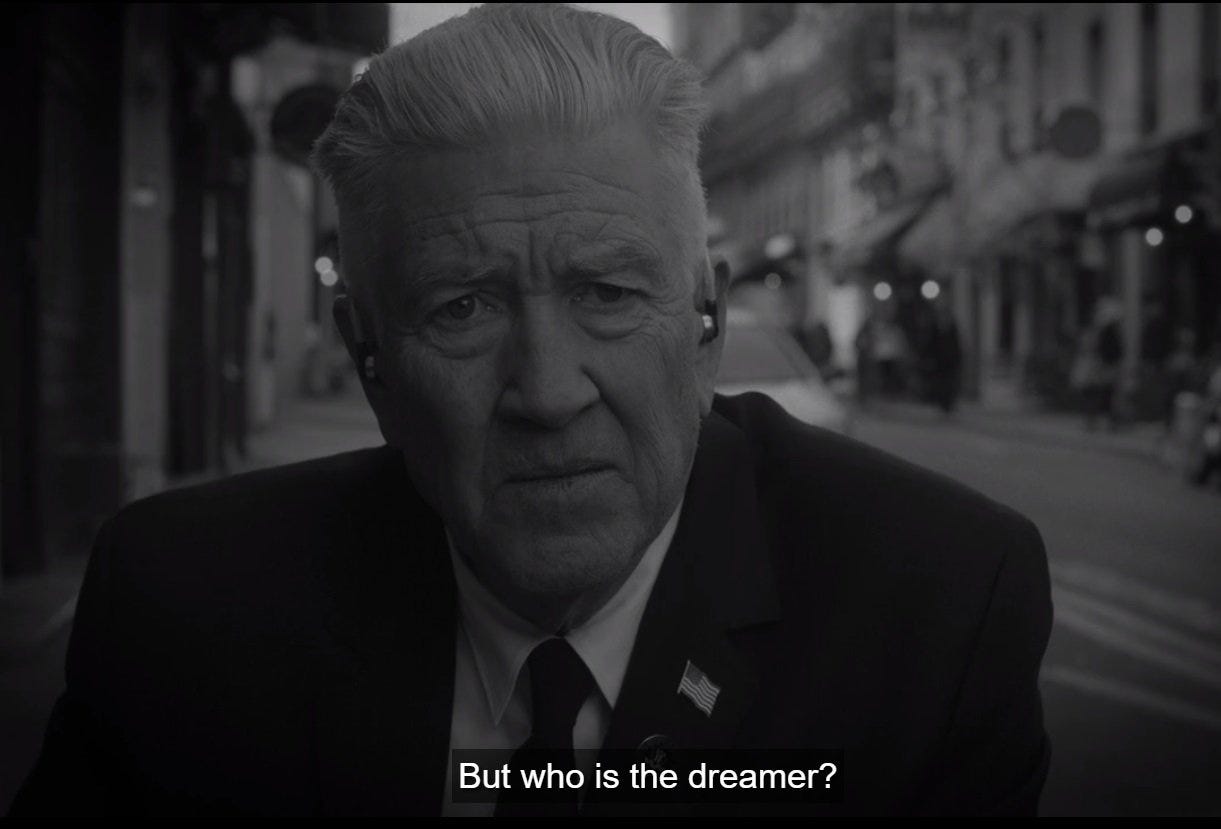

Do Not Break the Dream

As I talk about in the above-mentioned interview with Eli, in January of 2020 I checked into a bungalow at the Chateau Marmont in order to start writing my new novel EVERYBODY KNOWS. The Chateau is the hippest no-tell hotel in the world, and the bungalows are where the real dirt has gone down ever since Errol Flynn pretty much invented fucking there back in the day. I wrote the first chapter of the novel on Marmont stationary, and I wrote myself three notes on Chateau Marmont notepads. On one of them I just wrote the phrase “a vivid and sustained dream.” I think I got that phrase from Bird By Bird, one of the few genuinely good books about writing. (I’ve also adapted her concept of shitty first drafts into my mantra first you make it, then you make it good).

I explored some of this in my essay on creating a mood board in the first issue of Welcome to the Hammer Party:

The more I think about writing (and film-making and television), the more and more I become convinced that the sole job of a story is to create and sustain a shared, temporary dream. That’s it. That’s the whole deal …

What I really like about this definition of successful art is that it means that it creates a very testable subjective criteria for successful art: was the dream deep and sustained? Then the piece is a success. Does any given element break the dream? Then it is bad and should be removed. It doesn’t matter if it is an action film, an erotic thriller, a sci-fi epic, or a comedy. All that matters is that the reader/viewer is drawn in as deeply and fully as possible.

There’s a thing I do in movie theaters when a movie locks me in completely. I lean forward and rest my face in my hands, like I want my eyes as close to the screen as I can get them. When I do that, it means I’m fully in the dream. Inducing this state in your audience should be your sole intention as a storyteller. You can scare, them, thrill them, make them laugh - but you have to lock them in. And you don’t have to do anything else.

Right now in Hollywood there’s a common misguided notion that theme or message is the most important part of a story - that a story is just a delivery device for a moral lesson or message. It isn’t. A theme is a useful device for a story to have - I’d liken it to a bass line, something that gives your story heft and emotional resonance. Bass lines make music better - but songs don’t exist to deliver bass lines. They exist to be songs. Stories do not require outside justification to exist. A story exists solely to be a story, because people need them.

This logic leads me to believe there is only one rule to storytelling:

Do not break the dream.

It’s a rule with a million permutations and applications. A good plot twist makes the audience lean forward, drawn even deeper into the story. A bad twist wakes the viewer, forces them to do story math. A well-turned phrase will add to the all-important tone of the work, add subtle pleasure to the reading. A bad phrase knocks the reader out of the story completely.

Do not break the dream.

The first pages of a book, the first minutes of a movie, are of extreme importance. The opening of a story is a liminal space where you introduce your audience to the dream. It is a contract of sorts, in which every choice - syntax, tone, character, style, genre - is implanted into the mind of your audience. To violate those boundaries later in the story is to risk waking up your audience.

Do not break the dream.

Every choice matters. The dream is in the gestalt of the story, the way word choice and paragraph length and characters and plot and dialog weave into a whole enveloping world and tone (tone is so important). In film in it is light and sound and music and faces, the mise-en-scène that makes you forget you are looking at light projected on a flat screen. Any false choice at any level can ruin it all.

Do not break the dream.

And while the rule is ironclad, it is also wholly subjective - and that’s why they call it art, friendo. Every genre and format will have different boundaries, different paths you should follow (genre can be defined as a set of items that either should or should not appear in order to maintain the dream of the audience). Every viewer will have different desires, different tolerances, different prejudices and expectations. Your work is bound to not engage a sizable percentage of the world. You will try not to break the dream and for many people you will fail. You have to fail, it is inevitable. Brush it off, tattoo Born To Lose on your chest and keep robbing those liquor stores.

And the really bad news is, today the deck is stacked against the storyteller. Everybody’s antsy - a bad state to start dreaming. There is so much distraction, there are smaller and smaller screens. The Internet has taught the audience about tropes, and too many people have the idea that because something is a trope it is automatically bad, as if when Aristotle wrote his Poetics he was giving people a list of things not to do. Social media teaches a faux-sophistication that encourages audiences to engage with a story the same way that a cop engages with someone they are following on a dark road - waiting for an excuse to fire up the siren and start writing tickets.

And what are you supposed to do about all these disadvantages? Deal with them. Get better. Nobody said it was easy. Just get up in the morning, get to work, and do not break the dream.

Refilling the Tank: The Wolf House

The Criterion Collection has two outstanding collections of films on their site right now. Their Neo-Noir section is really outstanding, but also probably much more familiar to you than their similarly stellar Arthouse Animation collection. One of their most recent selections, The Wolf House, pushes the boundaries of stop-motion animation farther than anything I have ever seen, using paint, papier-mâché, tape, balloons, furniture and entire rooms to animate a folk tale about a girl hiding from wolves with a couple of pigs. It is strange and beautiful.

Murder Ballad of the Month

“Deep Red Bells” by Neko Case

Murder ballads, often written by men, tend to tell their stories from the perspective of the killer. Neko Case’s “Deep Red Bells” is a second-person song to the victims, “Those like you who lost their way/ Murdered on the interstate". The song makes full use of Case’s impossibly rich voice. It is soaring, somehow victorious, as she sings about these lost souls.

Writing Music - The American Analog Set, The Fun of Watching Fireworks

I got a chance to see The American Analog Set years ago at South By Southwest, and standing there in the crowd, I was so unsure what to do with myself I wound up sitting down and reading a book. It’s not that I was bored - I’d just grown so used to this band as the soundtrack to other things that reading a book seemed the right thing to do. I’ve been listening to The American Analog Set for more than twenty years now, over and over again, these impossibly gorgeous, hypnotic albums. I’ve used them for reading music, rain music, sleep music, writing music. The other day I walked into a Los Feliz coffee shop, all turmeric lattes and impossible twentysomthing cheekbones and funny hats, and “Gone to Earth” was playing over the sound system - not the incredible drawn-out version found on this album, but the cleaner, poppier take found on Know By Heart (kids today, am I right?) And it sent me on a trip, madeleine-style, to rediscover slowcore music, which was one of my great loves in the early 2000s. Most of my writing music is lyric-free - I always feel the lyrics will infect my writing - but on songs like these the words are just another part of the music. This is some of my very favorite music.

Okay, party’s over.

This is spectacular insight:

“ Social media teaches a faux-sophistication that encourages audiences to engage with a story the same way that a cop engages with someone they are following on a dark road - waiting for an excuse to fire up the siren and start writing tickets.”